The "Molecular Twin": How Laboratory Synthesis Reproduces The Geological Process

Lab-grown diamonds are often described as “synthetic,” but their defining feature is that they share the same carbon crystal structure as mined diamonds. Modern growth methods recreate the high-pressure, high-temperature conditions found deep in the Earth, producing a true material match rather than a look-alike. Understanding how these stones form, how they are graded, and how they move through today’s supply chain helps clarify what “same” means in a scientific and gemological sense.

A laboratory-grown diamond is not a diamond “substitute” in the way glass or cubic zirconia is. It is a crystallized form of carbon with the same fundamental lattice geometry that defines a natural diamond. What differs is the formation path: one is created over geological time through mantle conditions and volcanic transport, while the other is created in controlled reactors over weeks. For U.S. buyers, that distinction matters most in traceability, documentation, and supply-chain handling—not in basic material identity.

How does the atomic lattice align with natural carbon?

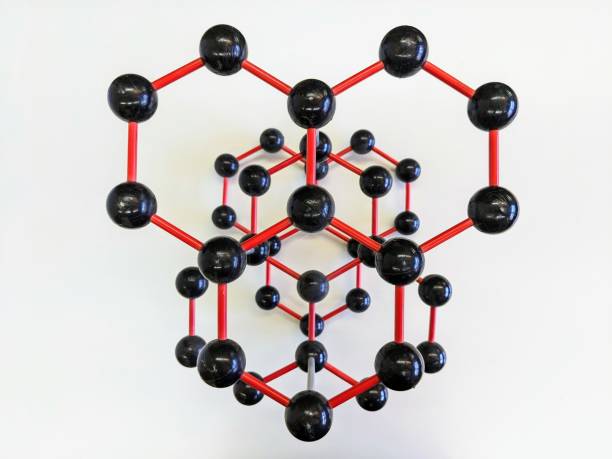

When people say a lab-grown diamond is a “molecular twin,” they are pointing to crystallography: how the atomic lattice of a laboratory grown stone aligns perfectly with natural carbon structures. In both cases, carbon atoms form a repeating tetrahedral network that produces diamond’s hallmark hardness and optical behavior. Because this is a structural definition, not a marketing claim, it helps explain why many standard tests focus on properties that emerge from the lattice itself rather than on where the crystal originated.

How does synthesis recreate mantle-like thermodynamics?

In practical terms, the synthesis process recreates the intense thermodynamic conditions of the earth mantle, but in a monitored environment. The two dominant approaches are High Pressure High Temperature (HPHT), which uses extreme pressure and heat to grow diamond from carbon sources, and Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD), which grows diamond from a carbon-containing gas plasma onto a substrate. Both routes are designed to produce diamond’s stable crystal phase, essentially compressing what nature does over long timeframes into an engineered process.

Why do optics and heat tests read the same?

Diamond’s signature look is tied to how it handles light: optical refraction occurs at the exact same velocity through both materials when the crystal is diamond with comparable purity and structure. The same is true for heat flow: thermal conductivity probes register the surface as genuine diamond without distinction because diamond’s thermal conductivity is intrinsically high relative to most other transparent stones. This is why the result is a material twin rather than a visual simulation or synthetic imitation; common screening tools are detecting diamond properties, not “mined origin.”

What does Type IIa mean for purity and defects?

A frequent point of discussion is classification: the classification of type 2a represents the purest form of carbon crystal rarely found in mining. Type IIa diamonds contain extremely low measurable nitrogen, which influences how the diamond absorbs light and can support a very colorless appearance. In controlled growth, the environment can be tuned so the controlled growth environment eliminates nitrogen impurities common in traditional stones, while also reducing some variability seen in nature.

That said, “purity” has multiple layers. Crystal growth can be managed so the structure develops without the chaotic stress fractures typical of volcanic pressure, but lab-grown diamonds can still have growth-related features (for example, certain striation patterns or metallic inclusions in some HPHT growth). The visual output achieves a colorless tier of transparency by default more often than many mined distributions, and for certain specifications the material integrity surpasses the random quality distribution of geological extraction—yet each stone still needs individual grading to document clarity and color outcomes.

How do grading standards verify shared composition?

From a consumer-protection standpoint, how leading gemological institutes apply identical grading standards to both categories without bias is central to marketplace clarity. Core grading factors—cut, color, clarity, and carat weight—are assessed using the same optical tools and measurement principles. Professional analysis utilizes standard magnification tools to map internal clarity characteristics, and reports record measurable attributes rather than stories about origin.

| Provider Name | Services Offered | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| GIA (Gemological Institute of America) | Diamond grading reports, origin disclosure for lab-grown | Widely recognized grading language; detailed cut/clarity documentation |

| IGI (International Gemological Institute) | Lab-grown and natural diamond grading | Common in retail supply chains; report-based verification of characteristics |

| GCAL (Gem Certification & Assurance Lab) | Diamond grading and verification | Emphasis on measured parameters and documentation practices |

Prices, rates, or cost estimates mentioned in this article are based on the latest available information but may change over time. Independent research is advised before making financial decisions.

Regulatory definitions recognize the shared chemical composition regardless of the formation source, which is why reputable documentation focuses on disclosure and measurable properties. In many cases, laser inscriptions provide microscopic verification of the specific growth origin (when a grading lab or manufacturer inscribes a report number or origin note on the girdle). The certification process documents the exact physical dimensions and optical performance, helping buyers compare stones using consistent criteria rather than relying on guesswork.

How has selection shifted to digital inventory analysis?

In retail practice, selection is increasingly data-driven: the selection methodology transitions from physical counters to high resolution digital analysis. Instead of viewing only what a local showroom has on hand, database filtering isolates specific cut proportions and clarity grades across large catalogs. This matters because the inventory visibility extends to global facility stocks rather than local display limitations, and high definition imaging reveals internal details often invisible to the naked eye—features that can influence brilliance, perceived transparency, and how inclusions present face-up.

Operationally, lab-grown supply chains can be more direct: the supply chain bypasses the heavy industrial requirements of excavation and ore transport, and the production timeline compresses geological eras into weeks of monitored synthesis. In some channels, the distribution network connects reactors directly to cutting facilities without intermediary aggregators, while the quality control protocol focuses exclusively on the structural integrity and optical uniformity of the crystal. In that context, the market trajectory favors technological efficiency over traditional extraction logistics, even as consumer preferences continue to vary by tradition, documentation expectations, and personal values.

Understanding “molecular twin” language becomes simpler when it is grounded in physics and grading practice: if the carbon crystal lattice is diamond, many defining properties will match regardless of origin. What remains different is the documented growth pathway and how that pathway shapes traceability, typical supply-chain handling, and certain growth-related features that a trained lab can recognize and report.